“I was taken in, I was tortured, the following day I was taken to Police Headquarters, and offered a deal. And the deal is, ‘We forget anything that happens, you go away, we drop you home, you stop speaking, ’ said noted photojournalist and activist Shahidul Alam.

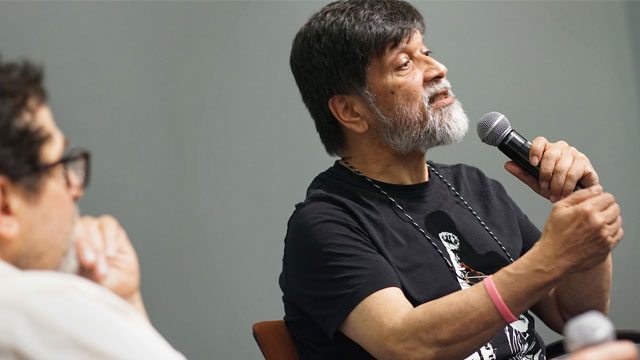

Shahidul Alam said this while talking about his arrest, torture made on him after that at the New York Portfolio Review, where Lens co-editor David Gonzalez led a discussion with him and the audience.

Shahidul Alam was in New York City recently to receive an Infinity Award from the International Center of Photography and address participants in the New York Portfolio Review. He took advantage of his stay to continue pressing for press freedom in Bangladesh, the New York Times reports.

“If you get beaten up and you shut up, then it’s O.K.,” he said. “The problem in my case was, I didn’t shut up.”

The following interview is from his appearance at the Portfolio Review:

Q: What advice do you have for younger photographers regarding today’s professional and political environment?

A: Most of us worry that we have disadvantages, be it color, location, whatever, we have things we need to deal with. I would turn it around and look at those very things as things that make us unique, things that separate us from the others. And it’s remarkable how we tend to overlook that.

We think, O.K., I am a particular type of photographer who is marginalized because these are the things I don’t have. But that very thing makes you unique in another way.

One of the things I talk to our photographers about is to do a resource mapping. And in your resource mapping the things that many people talk about — I have a camera, I have this or that — the fact that you happen to know that person who lives in the corner store who has that connection, whose uncle is something, is a unique advantage that you have that no one else probably has to that extent. Each one of us has some unique advantage.

Q: Your school educates many young photographers. Yet sometimes photographers ape previous incorrect narratives. How can they go beyond that?

A: I took on photography because I recognize its power in addressing issues of social change. I was looking for the best tool available, and at that point in time I thought it was photography. Photography continues to be a very powerful tool, though if I were starting today I would probably look at social media as well.

If I was to be effective in bringing about social change, I needed more warriors. So if you need more warriors, you build your soldiers, you train them. And that’s what the school was about. So the school took photography but not for the purpose of teaching shutter speeds and F-stops, but why one uses photography, why photography matters.

Right from the beginning, our emphasis has been on critical thinking, on analysis, on working out how one engages with those situations and how one uses photography. So I think while we teach the techniques, like you have to do at any level, I think right from the beginning students are considering why they do what they do.

Q: How do you get someone to start getting at their motivations, the why that they’re doing it, and how they develop their own perspective?

A: One of the things being done is constantly provoke the students. Push them. Test out their ideas. So one of the things they have to do is defend their ideas. None of us has a problem with their thinking differently, but we do have a problem with not being able to defend your position. And it is through that that you actually sharpen not only your photographic skills, but your logical skills, your argumentative skills, your persuasion skills, and at the end of the day you are being judged on the basis of how convincing you are to that other person. If as a communicator you cannot get your own ideas across, how are you going to get them across to other people?

Q: Going beyond diversity of photographers, how do you address representation in mass media, especially of people of color or marginalized communities?

A: It doesn’t really matter what you’re photographing, make sure that you do it with respect and with dignity. It might sound that I have problems with white press and photographers coming to our country and taking pictures. I don’t.

What I do have problems with is them having a monopoly on my story. But my point of view needs to be challenged just as much as everyone else’s. I suffer from the same blind spots that other people do. I also have biases and prejudices and they need to be questioned.

Plurality within the media is what gives it that richness. But having said that, I think coming back to being able to be respectful of the people around you, and that really is where the diversity comes in because often the stories are about people who are in a particular situation and a particular point of view in a particular crisis perhaps, and someone who knows them, understands them, empathizes with them, is far better placed to tell that story. And it is that empathy that you bring in that makes it unique.

Because at the end of the day, it is the person who holds the narrative who determines what the story is about. And we as photographers are those other people who hold that narrative. We are in a very powerful position. The onus is upon us to ensure that the story that we tell is respectful, is authentic, is what tells the story as it should be said, and does it with dignity. That should be our guiding mantra. Not what some other great photographer has done.

Q: Tell us about your legal case.

A: One of the things we were very concerned about was that a lot of people were getting disappeared and when they came out they said nothing. And some of these were our friends and we wanted to find out, and my partner and I decided we would make this a project where we try and find out what happened to people when they disappeared.

I didn’t realize I was going be the guinea pig and find out for myself.

Initially there were road accidents. A lot of students came out into the streets protesting. An Al Jazeera journalist asked me ‘Why such an outcry over road accidents?’ The point is, road accidents wasn’t the point, there was a lot of anger over a whole range of things happening, and this was the valve that let it through. And the students came out into the streets in protest.

I was taking pictures on the 4th of August, I got attacked, my equipment got smashed up, I got beaten up, because what the government did was they unleashed their goons to beat up the students. And that’s what I was photographing, so, that’s why they got upset.

The following day I continued reporting, I did my Facebook live updates and whatever. And then there was the interview on Al Jazeera, I finished the interview, then I’m uploading the material. I was actually talking to a BBC journalist for the interviewers getting ready for the next day, and the doorbell rings, I’m the only one in the house, and I look through the peephole, there’s a young woman with short hair and she calls me Uncle Shahidul, like this sort of, you know, one of my students. I opened the door, and then all these people from behind come up and there’s a huge number and I realized straightaway what’s happening.

Q: And then?

A: My first concern is that I want people to know this is happening because if they quietly take me away and people come into the house and find, ‘Oh he’s not there, what’s happening,’ by then too much time has passed. Those few minutes were very, very critical. So I screamed, I resisted, I did as much as I could to get attention. It didn’t delay or stop them, but it alerted people and then they knew something was happening by the time they came down I’d been picked up and handcuffed, blindfolded, taken away. But the buttons had been pressed. And that alert started to go around very very quickly.

I was taken in, I was tortured, the following day I was taken to Police Headquarters, and offered a deal. So I realized that this is what happens: You get this treatment and then you’re offered the deal, and generally you accept the deal. And the deal is, ‘We forget anything that happens, you go away, we drop you home, you stop speaking.’ So essentially, your freedom at the cost of your voice.

Q: But you didn’t stay quiet.

A: I wasn’t expecting it to happen at that time, but those are the risks we take. I was doing what we had collectively felt was each one’s duty. Essentially, the government had played out every trump card they had. This trick was, you give them hell, they cow down, and they stay quiet. If that doesn’t work, then in court they stay quiet. If that doesn’t work, you put them in remand and they stay quiet. If that doesn’t work you put them in jail. And what happens in jail is usually the family then calls a press conference, gives a plea to the prime minister for magnanimity and the prime minister releases the person through her largess, and the person comes out and thanks the prime minister.

None of that happened. I’m in jail 107 days, so much pressure that they eventually have to let me go. Outside of jail I continue doing exactly what I was doing before. I said what needed to be said, I continue to say what needs to be said.

I arrived yesterday at the airport, the first thing I did was to give an interview to a local Bangladeshi media on Infotube because in Bangladesh the mainstream media has largely abdicated. They no longer report as reporters have mostly become spokespeople for the government. So today, the alternative space is social media. And one of the most well followed pieces is this Bangladeshi channel called Bangladesh Infotube. So I made contact, they came to the airport to receive me. Before I did anything else, we did that interview and then I went on to other things. And I will continue to do that. That is my job. It involves risks and I think one of the things one needs to recognize is, as a journalist, your job is to stay at the edge. It’s where the heat is, if you go too far you get singed. You can’t walk too far back, you’re inactive. So that edge where you’re feeling the heat constantly is the only place where you belong.

Q: How did you spend your time in jail?

A: Over the 107 days I was there, one of the things I was able to do with the help of other prisoners, we had murals drawn, faces, on the walls of the jail, so there are over 40 murals painted on all the side walls. One picture some of you may have seen, a picture of the red sailboat, which is quite a well known picture of mine that’s been on National Geographic and many other places. The prisoners painted that as homage to me on the wall, so there it is, that’s my proudest publication.

They told me, could we have musical instruments. So I sent out an appeal. Friends of mine sent musical instruments. They formed a band. I’ve got messages that they’ve written 40 new songs, they’re recording. We planted a vegetable patch so they now have fresh vegetables. We started adult education classes. We now have over 200 students and the hall cannot accommodate everyone. In the band, the warden’s joined the band and become a guitarist in the band. So we can turn the whole thing around. Every opportunity you have, you turn it around.

Q: Are other Bangladeshi photographers in jail, who deal with social issues, who are also imprisoned or were imprisoned?

A: There are many people who gave likes on my Facebook post and shared my Facebook post who are still in jail. Now we are challenging the validity of section 57.2, which is what I was accused of. Essentially, it means that if someone in electronic media, digital platform, says something which goes against the government or offends their sensibility — it’s a very sweeping thing — the government can arrest people without warrant.

We did protest against it and the government replaced that bill with the digital security act, which is actually worse. But what has happened is, despite the fact that that particular law has been repealed, people like me still have been jailed on the basis of it. And if, as seems plausible now, the court rules in my favor, that would open an entire floodgate where all these people who are in jail will then be able to be released.

Q: Does the spotlight that you are in right now affect your own photography?

A: I’m still in danger. The case still hangs so I still potentially face 14 years in prison. More significantly, on an everyday level, the way I operate is very different. I go around on my bicycle, I stop in the street, I talk to people. I work in a very organic manner. Now it’s no longer safe for me to do that because when I was being attacked on the 4th of August, I was just one person taking pictures.

Now the spotlight means that I am visible and they know that I am a threat to the government. So there are lots of people out there who would want to get Brownie points. Getting rid of a bad guy would give them credit with the government. So I can’t take that risk, so I’m not cycling, I don’t walk on my own, I’m never on my own, I drive to places, I have other people with me. And that all just impinges on the way I work and what I can do.

Q: Journalists in the United States benefit from a certain level of protection where we don’t necessarily have to think about a lot of these things when we’re working in the States. Does your role shift when you’re here, and should we be thinking about our role differently?

A: You say you’re in a position of better protection. I think you suffer from a level of complacency. If I were in this place, I would really worry a lot more. The average American — it might not be true for some of you — but when I talk to people in the street, I’m amazed by how ignorant they generally are.

People in Bangladesh are far more politically savvy. Honestly, over here, the issues are far more about houses and mortgages and careers and all this sort of thing and not about the bigger issues. There are not that many people who engage with the world as such, not many people know the rest of the world. The problem here really is we are in a zone of comfort to such an extent that we’re insulated from that position, and that to me is a bigger fear.

If I were here, I would need to work a lot harder to ensure that I was still at the edge, because stepping back is so much easier. And no one worries about it, you’re applauded for doing well in your career, you’re applauded for having that mortgage, you’re applauded for building a house or whatever else. The fact that you’ve not done what you were meant to do, that as journalist your position is to be there on the line.

Honestly, I feel fortunate that I am in a country like Bangladesh as a journalist, because I don’t need to look for a cause, I’m surrounded by them.

YS